Download a printable version of What to Expect when Accessing Records about You (1.2 MB PDF)

If you (or a member of your family) spent time in ‘care’, there will likely be records that are personal to you, and your story. In Australia, the state government and community services organisations are the ‘custodians’ of these personal records about children in ‘care’.

You won’t see these records on a website, or in a book, because they are private, personal, and confidential. But if the records are about you, you have the right to ask and to access them.

People seek out their personal records for different reasons – everyone’s story is different. It can take a long time to actually make the decision to approach an organisation and ask about your records.

We hope that the information here will assist you on your journey to find out about your time in ‘care’.

Like many older care leavers, I was not even aware that files were kept about me until I was in my mid-fifties. [Frank Golding, ‘Telling Stories: accessing personal records’, in Hil & Branigan (eds), Surviving Care: Achieving justice and healing for the Forgotten Australians, Bond University Press, 2010].

People often embark on the journey to locate and access their records expecting to:

But, many of these common expectations will not be met when you locate and retrieve your records.

If you were a state ward, there may be some form of wardship records about you held by the state government.

If you were not a ward of the state, there may be records held by the non-government agency that holds the records from your ‘care’ provider. In some instances, the available records may only be the admission and discharge record.

Past record keeping practices of Government departments and ‘care’ providers were primarily for administrative purposes rather than to keep an accurate record of all events. Unfortunately, the older records may be superficial, inaccurate, or incomplete, and leave many questions unanswered.

The records kept and the information recorded will vary according to the time period when you were in ‘care’, what sort of institution you were in, the policies and practices of different ‘care’ providers, and even the personal habits of different staff members keeping records.

Some people find that their years in ‘care’ only generated a few lines of writing. Other people are presented with reams of information (although it will not necessarily be an accurate reflection of one’s experiences).

Many people who read their records don’t expect it to be such an emotional experience and are not prepared for the significant emotional impact including feelings of anger, and hurt, but also sometimes feelings of confirmation or relief.

Some people find that their files are not just full of bureaucratic facts and figures but contain records that evoke the pain of a child being removed from family. Sometimes the contents of your file will contradict the way you remember the past. It might contain information that was kept from you as a child, or reveal that you were lied to when you were in ‘care’, e.g. finding letters from family members that were never passed on to you, or letters that you had written.

The records often contain negative, derogative, and even offensive language, to describe the child and his or her family. As Frank Golding writes:

Many of us find our personal records are almost entirely negative. Care Leavers often search their records in vain for positive achievements, but the archives are brimming with examples of our minders’ low expectations. Some of us who are perfectly intelligent have found in our records that we were described as ‘slow-witted’, even ‘low-grade mental defective’.

[Frank Golding, ‘Our side of the story’, published 17 June 2016, Frank Golding blog, URL: http://frankgolding.com/our-side-of-the-story/ (accessed June 2016)]

The process of seeking access to your records can lead to positive experiences. You can find clues and answers to these identity questions by locating and accessing records about your time in ‘care’. Records can sometimes help if you have gaps in your own personal history, especially about your childhood. Also, it can lead to reconnecting with friends from your childhood. Some people find it helpful to attend reunions of the home where they lived as children, or get-togethers organised by support groups for ‘care’ leavers.

Many people have found that the experience of accessing your records has a significant emotional impact, bringing up feelings of anger, hurt, fear, but also sometimes feelings of nostalgia or relief. The search for your records can be complicated and frustrating – but there are many different organisations that can help you find out information about your time in ‘care’, locate and access any personal files that might exist, and give you support throughout the process.

If you are not sure where to start your search for records, or you want some support through the process, we suggest you get in touch with an organisation who can help. See Find & Connect Support Services. There is support available for care leavers searching for family or wanting to meet and share stories with others with whom you were in ‘care’. Some support groups also advocate on behalf of ‘care’ leavers or provide counselling.

If you were a state ward (or ‘ward of state’), it is likely that the state government has some wardship records relating to your time in ‘care’. Various documents were generated in the process through which a child was deemed to be a ward of state, including court records, police records and departmental records.

Wardship records were created and kept as administrative records to help the department manage its affairs. The records generally relate to matters such as court appearances, admissions and discharges from institutions or foster care placements and maintenance payments by a parents. During most of the twentieth century, wardship records were very bureaucratic. People getting their records as adults can be shocked and disappointed to see how little information there is about the child and their family situation.

In his book Children who need help (1963), social worker Len Tierney described how welfare departments thought about recordkeeping:

For good or bad, the child went forth into the unknown, a receipt for his person secured, and a brief history of the child sent to the Superintendent of the institution. This history was no more than a précis of the Police complaint, a statement of the court decision, and an itemised account of the disposal of the other children in the family. There the child would remain, and for practical purposes the file was closed, until it became necessary to remove him from the institution. For the time being, the Department had fulfilled its legislative functions, and no further action ensued until it was necessary to make a new decision about his disposal.

Attitudes to recordkeeping in children’s Homes run by charitable and church organisations were not very different from government departments. A report from Victoria in 1957 spoke of “the absence of all individual records in some institutions and of adequate records in most”. Different Homes had different approaches to keeping records, and it’s likely that various staff members kept various kinds of records.

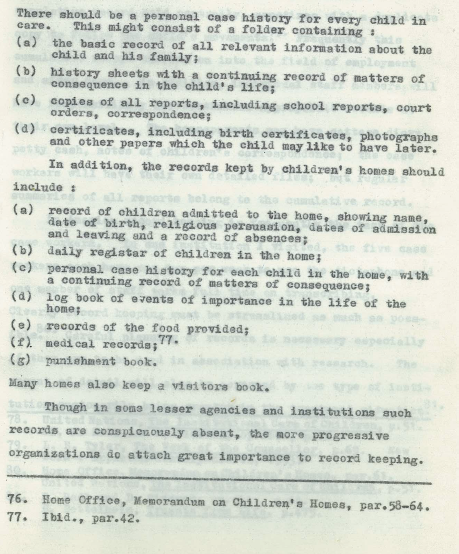

One Superintendent, Keith Mathieson, wrote about what we would now call “best practice” in recordkeeping in 1959. In the late 1950s, Mathieson’s views about what records needed to be kept for children in ‘care’ were the exception, not the rule.

Unfortunately, it is very unlikely that a person applying for their records would receive a ‘personal case history’ like the one described by Mathieson, with a ‘continuing record of matters of consequence in the child’s life’ and copies of documents like school reports, birth certificates, photographs and ‘other papers which the child may like to have later’.

A more common experience is to receive records that are quite minimal. One person described his experience to the ‘Forgotten Australians’ inquiry:

After 18 years as a ‘Ward of the State’ and some 32 years later, I finally get enough nerve to have the audacity to ask the system for whatever relevant details they may or may not have on me during my childhood … I get two sheets of paper with about 9 or 12 lines on it, I look at these two sheets and I am devastated, 18 years of my life on two sheets of paper. I ponder and wonder this can’t be all of my 18 years on two sheets of paper.

Unfortunately, not every person who was in ‘care’ will be able to find and access their records. In the past, records have been lost and even destroyed, meaning that vital and precious information is not available. Even if you are one of the people whose records no longer exist, there are other historical records that might contain information that helps you to understand your time in ‘care’ – newspaper articles, photographs, books and oral histories can be valuable resources. This Find & Connect website has information from these types of resources relating to particular homes, organisations and events.

The Find & Connect contains information about a range of historical resources that can help you understand and interpret the information on personal records. Finding out more about the historical context can help you understand more about the ‘why’ and hopefully lead to some healing, and an end to feelings of self-blame due to being bewildered about the past.

Many care leavers have written their own histories. These memoirs and autobiographies provide the history of child welfare from the perspective of the people most affected. Inquiries like Bringing them home, and Forgotten Australians received hundreds of submissions from people who had been in ‘care’ as children, and you can read their stories on the web.

In Find & Connect, you’ll find information about books, articles and websites that provide historical background about homes, organisations, and child welfare in general. Where these sources are available on the web, you can follow links to them from Find & Connect.

The world wide web is a great resource for the ‘historian of the self’, and its collections are ever-expanding. A great place to start exploring is Trove, at the National Library of Australia.

Information about you or your family might also be found in historical sources not necessarily to do with the ‘welfare system’, eg

Genealogical societies and online genealogical resources can be a good source of information about these types of records.

The importance for all of us having a story about our origins helps explain why accessing records is so crucial for those who grew up in institutional care; many become historians of the self.

[Murray et al, After the orphanage: life beyond the children’s home (2009)]

Learning about your time in ‘care’ through accessing records isn’t just about the information recorded in your personal or client files. There are other types of records held by organisations which can help you to fill in the gaps about your time in ‘care’. As well as ‘personal records’ like admission records and case files, you can also get access to ‘organisational’ records (such as annual reports, minutes of meetings, and photographs). These can give important background information about the institution where you lived, and help you to contextualise and make sense of the details on your personal file. This context that comes from organisational records can be just as valuable as the records on your personal file. So you can think of the organisational records of a ‘care’ provider as being one element of ‘your’ records.

These type of records give information about staff members who were employed at different periods in time, about the governance of ‘care’ providers, and background about the key decisions made at the institution while you were there. Although it is not always the case, information about particular children sometimes appears in these types of records.

The superintendent of an institution was often responsible for making regular reports with details of occurrences at the institution. The names of children and details of a particular incident can sometimes be found in superintendent’s reports.

Annual reports can be a rich source of information about an organisation, and the institutions and out-of-home ‘care’ programs it ran. They often contain photographs of buildings as well as people. Annual reports contain information about the finances and governance of an organisation, and ‘news’ from the previous year.

There may be photos and other information in annual reports that tell you about your life, but it should be said that some of these reports and histories focus only on the people running the organisations and the issues that were important to them, like financial affairs and staffing matters.

The content of annual reports, including photographs, tends to put the best face on the way the Homes were run. The voices of children are very rarely heard and negative events are often glossed over or ignored. As one historian writes: ‘annual reports are political documents; they reveal what they are designed to reveal, and obscure with aplomb what they do not intend to expose.’ (Lynne Strahan).

Regardless of the ‘spin’, the statistics in the annual reports are generally accurate, and can provide insights into how children in need of ‘care’ were treated, and how external circumstances (like war, epidemics, economic circumstances) could affect children’s welfare. Annual reports are a very valuable resource, if you can approach them with some degree of healthy skepticism, and try to read them ‘against the grain’. They are also records which are likely to have been kept and preserved by an organisation, or even housed in some public library collections.

Many of the major ‘care’ providing organisations have had their histories published. This often coincides with an anniversary or milestone in the organisation’s history. In many cases, these histories have been ‘commissioned’ by the organisation itself. Because of this, and for the reasons outlined above when discussing annual reports, organisational histories sometimes have to be taken with a grain of salt. They may put a very positive spin on a history that you remember quite differently. They may emphasise the stories of staff members and benefactors, rather than the lives of the children being ‘cared’ for. But, published histories contain a lot of information about organisations, their timelines, their changing approaches to child welfare, and can be a digest of precious photographs and documents held by the organisation in its archives.

Organisations that provided ‘care’ to children (like children’s homes and orphanages) created records to help them in their work. If you spent time in an institution as a child, there may be records about your time in ‘care’ that have been kept. You can access these records.

These records can be a valuable source of information about you, your childhood, your family and the story of your time in ‘care’.

There is legislation that applies to your right to access records. Different laws relating to privacy and freedom of information apply in each state and territory, and depend on whether the records are in the custody of a government department, or held by a past or current care provider organisation.

Legislation in each state requires the government to keep the personal records of children who were in ‘care’ permanently. Usually the internal policy of an organisation states that the ‘care’ provider must also keep its client files permanently. Inquiries like ‘Forgotten Australians’ and ‘Bringing them home’ have also stipulated that these records are never to be destroyed.

The organisation that created the records needs to be accountable for its actions as your former guardian, and in many cases will have kept the original copies of the records. In the case of some records on your file (like personal letters, school reports, photographs) you can request the community service organisation give the original records to you, and keep a copy for its files.

The government or a community service organisation might be the custodian, but you have a right to request access to records if they contain information about you.

You may also be given the opportunity to add information to the files an organisation or government department has about you, as a way of completing the picture, and making sure that your voice is included.

In the case of other people’s records, for example a sister or brother or a parent, you can access those parts of the file that contain information about you. You might find that your access to some information in the records (yours and other people’s files) is restricted, because of the interpretation of privacy or freedom of information legislation. Usually, it is information about ‘third parties’ – meaning people other than yourself – which you may not be permitted to see.

The need to protect third party information is sometimes at odds with the need people have to find out information about family members, and their past. In the case of government records, there are formal avenues to appeal any information that is exempted from the file and these appeal rights are outlined when records are provided. See also Applying for Records: Your Rights and the Law.